Introduction

Given the complexity of SLE, its clinical presentation may imitate other diseases, including autoimmune thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, myasthenia gravis, scleroderma, antiphospholipid syndrome, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and scleroderma.

The most common clinical symptoms in patients with SLE are musculoskeletal problems. Joint pain, pain in the wrist, and knee pain are among the most frequently reported symptoms. Myopathy, osteonecrosis, and arthritis are also reported. Approximately 5%–10% of patients with SLE have antibodies to citrullinated peptides, and these antibodies are associated with erosive arthritis (

Budhram et al. 2014;

Di Matteo et al. 2019;

Jung et al. 2019;

Metry et al. 2019;

Malekan and Kontzias 2020). Dermatological manifestations are another clinical symptom and include malar rash, discoid rash, livedo reticularis, lupus profundus, vasculitic purpura, urticaria, and telangiectasias. Although alopecia with patchy loss and butterfly rash are among the prominent signs of this disease, it is not sufficient for definitive diagnosis (

Cojocaru et al. 2011). Lupus nephritis occurs in most cases of SLE (

Zheng et al. 2019). Gastrointestinal findings, as well as cardiac and vascular manifestations are also common. Takayasu’s arteritis and Raynaud’s phenomenon occur in a small majority of SLE patients. Similarly, keratoconjunctivitis sicca is an ocular manifestation that has also been reported. Obstetric manifestations may cause spontaneous abortions and fetal retardation. One of the most important findings in SLE patients are endocrine manifestations, including thyroid dysfunction, of which middle-aged and older women are at higher risk (

Wang et al. 2019). Similarly, lymphopenia, leukopenia and hematologic manifestations often occur as well (

Jung et al. 2019). Pulmonary manifestions include pleurisy, dyspnea, hemoptysis and thromboembolic diseases (

Kokosi et al. 2019). Neurological effects have also been reported. Studies have shown that the incidence of antiphospholipid antibodies in SLE patients is high (

Ben-Menachem 2010).

SLE causes psychological problems associated with depression and anxiety, causing psychological behavior patterns (

Moses et al. 2005;

Mendelson 2006;

Monaghan et al. 2007;

Budhram et al. 2014). Anecdotal reports suggest that SLE is associated with high vulnerability and patients can experience emotional and psychological issues, especially during the treatment process (

Iverson 1995;

Druley et al. 1997;

Santoantonio et al. 2006;

Schattner et al. 2008;

Andrews et al. 2009;

Shucard et al. 2011). Acute confusional state and psychosis occurs less frequently than other symptoms (

Hanly et al. 2019). Certain neurological dysfunctions may also result in a decrease in the individual’s ability to focus. Visual-auditory hallucination in SLE patients can result in psychosis (

Kang and Mok 2019). Cognitive dysfunction such as psychomotor speed or memory disorders, including pain and sleep problems, may also occur. Together, the combination of these symptoms can cause mood disorders, and are associated with manic or depressive episodes (

Ainiala et al. 2001;

Meszaros et al. 2012). Anxiety is more likely to occur in those with SLE than in normal healthy individuals. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic disorders have also been reported (

Papadaki et al. 2019). Fatigue, irritability and sadness are also prevalent. All these symptoms and factors decrease the quality of life of patients with SLE.

Neuropsychological effects adversely affect the behavior of SLE patients. These negative psychological behavior patterns can become even more pronounced during aging, a process defined as an individual’s cognitive, mental, psychological, psychosocial, physical, biological and social decline. Palliative diseases have been found to affect the self-perception of aging. According to clinically determined findings, the psychological and physical effects of disease in palliative patients affects self-perception of aging (

Richardson 2002;

Rodriguez et al. 2007;

Hupcey et al. 2009;

McLaughlin et al. 2011), and decreases quality of life. These effects are similar to the neuropsychological symptoms of SLE, and raises questions of a possible association between SLE and self-perception of aging.

To date, there are no convincing studies on the pathological causes of behavior patterns that SLE patients experience. Further, the psychological effect of SLE on self-perception of aging has not been investigated. Here, we sought to assess the perception of aging in 4 related families and spouses who were directly or indirectly affected by SLE.

Results

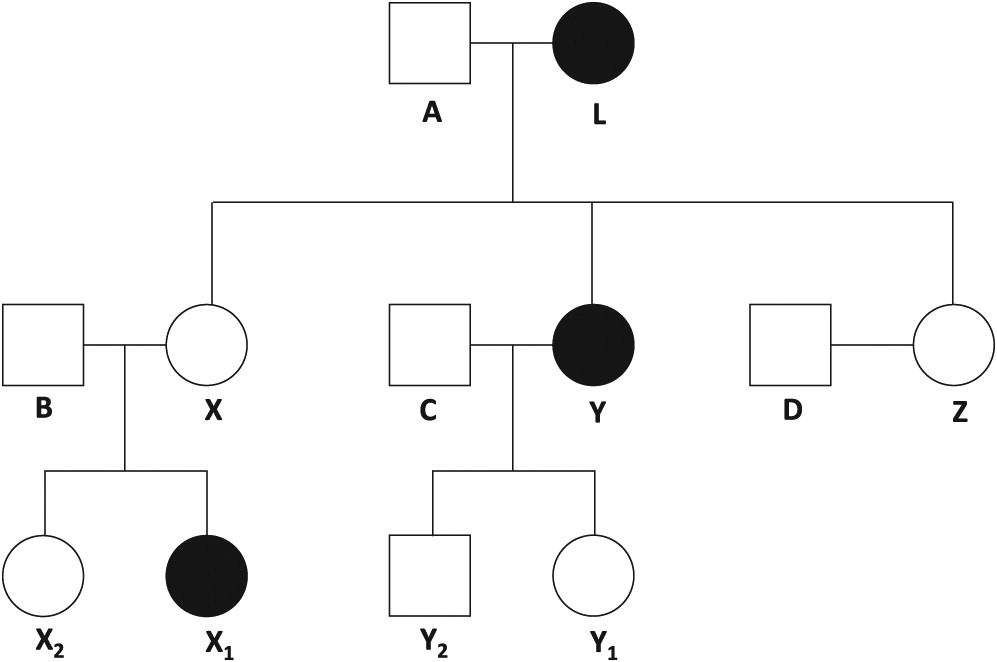

The 7 female and 5 male participants were members of 4 related families living in the province of Adana, Turkey (

Figure 1). The maternal grandmother (Pt L), daughter (Pt Y), and grand-daughter (Pt X

1) were clinically diagnosed with SLE. Two daughters (Pt X, Z) and 3 grand-children (Pt X

2, Y

1, Y

2) did not have SLE. Similarly, none of the spouses (Pt A, B, C, D) had SLE. Participant demographics are shown in

Table 1. None practiced regular exercise. Each revealed that their family relations were good, there were no smoking habits and alcohol was rarely consumed. None of the participants had suffered a major loss or traumatic event in their history.

Review of medical charts and results of the questionnaires revealed that, although Pt X, X

2, Y

1 and Z did not have a clinical diagnosis of SLE, they had similar complaints and disorders as the family members with SLE (

Table 2). Further clinical assessment (anti-nuclear antibody, anti-dsDNA, cryoglobin and complement c3 testing) did not support a diagnosis of SLE in these participants. All participants, with the exception of Pt Y

2, had severe anxiety and phobia predisposition (

Table 3).

The participants with confirmed SLE were asked about their diagnosis of SLE and their perception of aging. Each believed that there was a relationship between aging and the non-resolution of complaints. One participant’s response was: “My complaints are increasing due to my illness. I think I’m getting old.”. Another participant stated: “My life was ruined because of this disease. I have constant joint pain. As my pains increase, I remember the complaints of old people. I think I’m getting old.” All participants indicated that they preferred to give up struggling with their diseases and disorders, as their complaints could not be solved despite visits to the doctor. Participants often felt this way when the pain became unbearable. Some statements from the participants were as follows: “This disease is killing me day by day. Treatment and medications are insufficient. I feel old. This desperation overwhelms me.”, “My husband is my biggest supporter. But he is not able to do anything. I have all the complaints of the elderly people around me. I am not different from them.”

When the same questions were asked to the female participants who had not been diagnosed with SLE, but had symptoms of this disease, they stated that they were very anxious about having SLE. Statements include: “I am very afraid of lupus. After all, this disease seems to be taking over the whole family. We have the same complaints as my sister and my mother. From time to time we talk among ourselves. We’re evaluating my mother’s and sister’s complaints. I worry about them.”

The husbands of Pt L, X, Y, and Z (Pt A, B, C and D, respectively) were included in this study to assess the effects of SLE on psychological transitivity. Psychological transitivity is the ability of individuals to subconsciously imitate the psychological behaviour patterns of physical states and movements, including diseases, such as SLE (

Dai 2017). In this qualitative study conducted with husbands of the participants, we found that each spouse experienced psychological problems; their phobia susceptibility increased, and they did not experience these complaints before their marriage (

Table 3). Some responses from the participants were as follows: “I did not have psychological problems before I got married. I love my wife. But I also feel the same pains from time to time because of her constant pains. I think I’m starting to look like her.”, “Even when I was in the army, I didn’t have that much stress. Everything was fine in the first years we got married. Later, my wife’s joint pain began to exacerbate. Pain in the kidneys and headaches gradually gained momentum. Going to a doctor continuously has worn me out. When I take her to the doctor, I go too. What’s the difference between us? I think this disease is contagious. I also experience her complaints from time to time.”

Pt A, B, C and D were noted to have digestive and stomach disorders, as well as hemorrhoids (

Table 3). Each stated that their life quality was decreased, due to constant medical check-ups. Some of the responses to the interview questions include: “Going to the doctors to check-up continuously and seeing that there is no solution reduces your joy of life. Imagine that your partner is melting away in front of you, has constant pain, please think about it. My mind is always with her. Your quality of life is completely under zero.”, “After my wife’s pain started, I started to experience a stomach pain. I am constantly getting constipated. When I went to the doctor, he said it was psychological. This affects my life in a negative way.”

Discussion

In this study, we found that the psychological effects of SLE increased the self-perception of aging, with the participants reporting themes of “feeling old”. Individuals with SLE related their symptoms in a similar way to the physical and psychological decline that occurs with aging. This aspect may be an important neuropsychological determinant in SLE. Female participants who were not diagnosed with SLE also reported the same or similar complaints as their family members who did have an SLE diagnosis, including tingling in arms, legs, feet and shoulder, arthritis pain, sadness, stress, crying (emotional incontinence), anxiety, nervousness, the status quo of unhappiness, not enjoying life, feeling old. Since SLE is more common in females than males, it is important to explore whether female relatives of affected individuals may have SLE.

We found that the complaints of Pt L, X1 and Y, who had a diagnosis of SLE, were pain and psychological based. Nephrotic syndrome, urinary tract infection, weight disorders, and the need for psychosocial support were common in the medical history of these participants. While the other participants did not have SLE, their similar health complaints creates an important perception about SLE. This perception causes psychological problems and affected the spouses in this study negatively.

Various phobias were noted in spouses of the participants: Pt A: aichmophobia, pharmacophobia, iatrophobia; Pt B: pteromerhanophobi, claustrophobia; Pt C: hemophobia, carnophobia; Pt D: atychiphobia. These psychological disorders emerged after marriage, and may be associated with long-term stress and anxiety (

Fox et al. 2005). Furthermore, the spouses each complained of digestive and stomach disorders as well as hemorrhoids. Together these demonstrate the negative impact of SLE on the psychological and medical problems that occur after marriage to a person with SLE.

The pain imbalance experienced by SLE patients should be evaluated in terms of neuropsychological aspects, and recommendations should be made to treat the psychological problems experienced by spouses of patients with chronic diseases.

This study had some limitations, including possible prejudices of the participants. Presenting the views and situations of the participants with predetermined questions limited the generalizability of the results. Thus, it would be important to perform such studies involving participants with different demographic characteristics. It may be of interest to repeat this study with palliative patients and their spouses, since palliative diseases include chronic neurological diseases (such as dementia). This would help to better understand self-perception of aging and psychological transitivity in these diseases (

Anneser et al. 2018).