Background

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is a primary immunodeficiency that affects an estimated 1:200 000 live births (

Holland 2010). It is caused by defects in the phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, which is required for respiratory burst activity and killing of microorganisms (

Roos et al. 2003). Thus, while phagocytes are able to ingest invading microorganisms, in the absence of respiratory burst, they are unable to kill them. Mutations in any one of the 5 genes which encode the complex can result in partial or complete ablation of function (

Kuhns et al. 2010). These include the membrane localized gp91

phox and p22

phox, encoded by

CYBB and

CYBA, respectively, as well as the cytosolic components p47

phox, p67

phox, and p40

phox encoded by

NCF1,

NCF2, and

NCF4, respectively. Defects in gp91

phox result in X-linked inheritance and affects an estimated 65% of cases in North America (

Winkelstein et al. 2000), whereas mutations in p22

phox, p47

phox and p40

phox are passed on in an autosomal recessive manner. Rarely, X-linked inheritance of CGD is found in females due to lyonization (

Roos and de Boer 2014;

Marciano et al. 2018).

Patients with CGD usually present within the first 3 years of life with difficult to treat recurrent bacterial and fungal infections (

Thomsen et al. 2016), especially from catalase-positive organisms which degrade hydrogen peroxide and further hinder the microbicidal activity of affected phagocytes (neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, eosinophils) (

Ben-Ari et al. 2012). Infections are commonly associated with the bacteria

Staphylococcus aureus,

Serratia mercescens,

Burkholderia cepacia,

Nocardia,

Streptococcus,

Salmonella species, and

Klebsiella species, while

Aspergillus fumigatus and

Candida albicans are the leading fungal culprits (

Ben-Ari et al. 2012;

Falcone et al. 2012). As a result of the recurrent infections, patients with CGD develop lymphadenitis, abscesses, and granuloma formation. Other manifestations include osteomyelitis, purulent dermatitis, and cellulitis.

Histopathology is an important aspect of the work-up for CGD, assisting to determine the composition of cellular infiltrates, extent and severity of tissue injury, as well as identity of invading bacterial and fungal organisms. Various organs may be affected, including the gastrointestinal tract, liver, skin and soft tissue, lung, bone, bladder, and lymphoreticular systems.

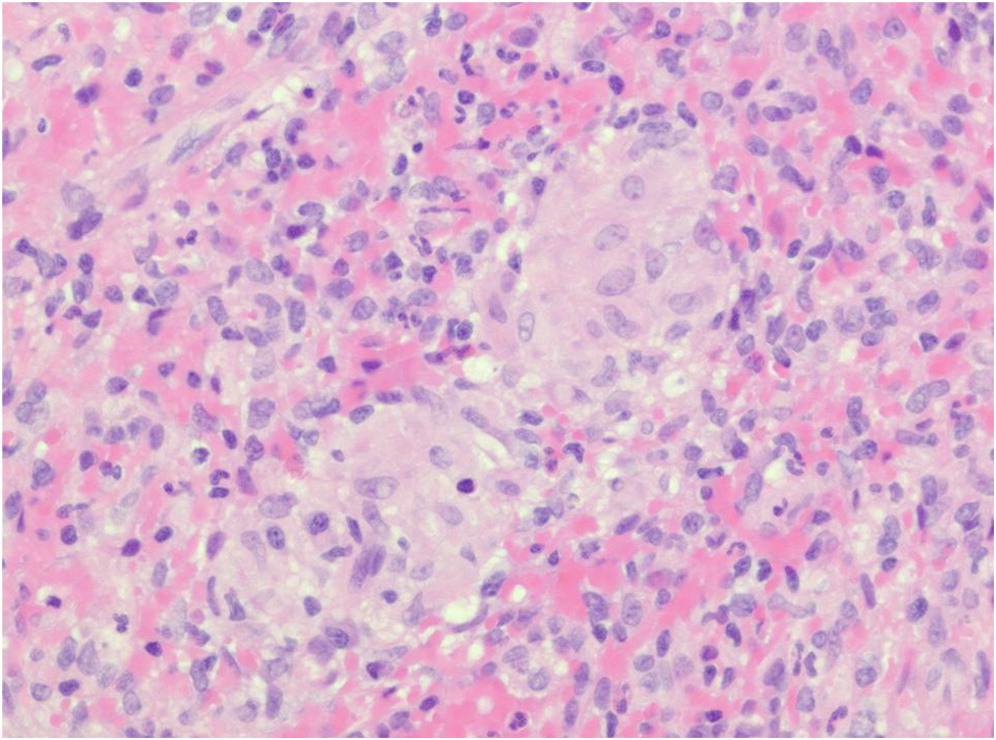

Non-caseating (non-necrotizing) granuloma formation is a hallmark of CGD and may appear in the lungs, liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and skin (

Schappi et al. 2008). Non-specific abscess formation or acute inflammation is often present, alongside accumulated pigmented macrophages (

Levine et al. 2005). While histopathology alone is insufficient to provide unequivocal indication of CGD, it can be used to raise the suspicion of disease.

Here, we present histopathological findings from 5 paediatric patients with confirmed diagnosis of CGD.

Discussion

Infections in patients with CGD are often associated with organs that are exposed to the external environment—including skin, lungs, and GI tract, as well as the lymph nodes where foreign antigens are processed. Furthermore, dissemination of microorganisms can result in liver abscesses and osteomyelitis. The results of histopathological findings can raise the suspicion of CGD and help to distinguish it from other childhood diseases that may affect similar organ systems. While there are often common findings of non-specific acute and (or) chronic inflammation, granulomatous inflammation is identified in up to 40% of cases (

Levine et al. 2005). Granuloma formation is a classic feature of CGD, and is thought to arise from the immune dysregulation associated with ineffective phagocyte killing and persistent recruitment of macrophages. Hyperinflammation and autoimmune phenomena is common in CGD patients, and has been attributed to abrogated anti-inflammatory signaling. Often, pigmented macrophages containing inadequately digested intracellular debris are also present in affected tissues. Here, we highlight the histopathological findings in 5 patients with genetically confirmed CGD.

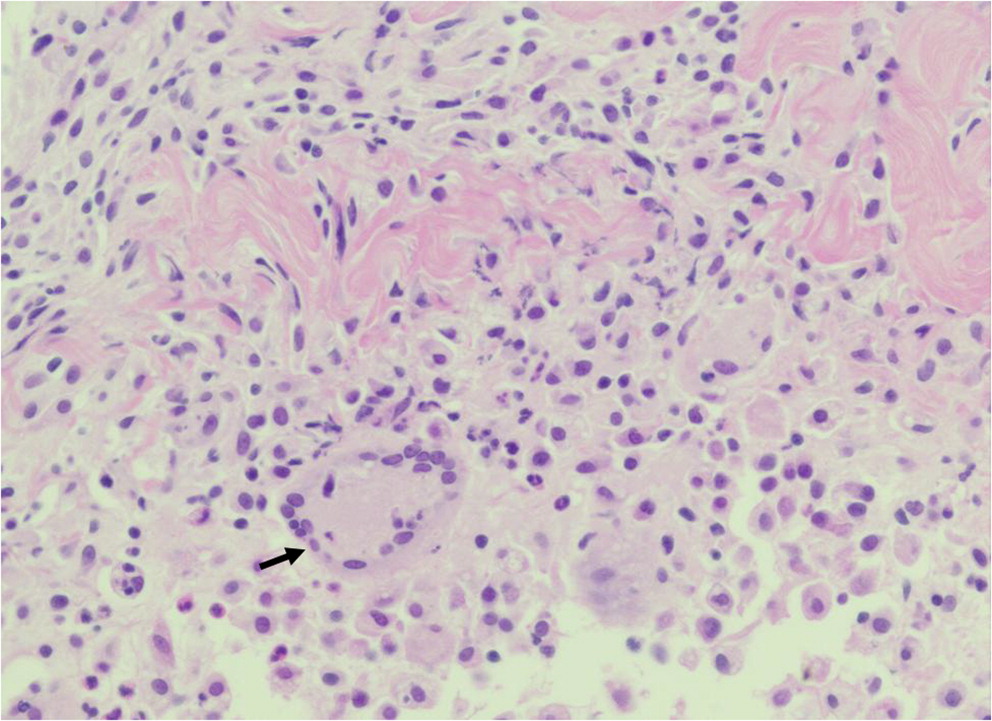

An estimated 90% of patients with CGD have hepatosplenomegaly, and abscesses in the spleen or liver may also occur (

Zimmermann 2016). Splenic biopsy from patient 1 identified the presence of non-caseating granulomas. In the absence of other infectious etiology, a diagnosis of juvenile sarcoidosis was made. However, subsequent repeat low neutrophil oxidative burst indices raised the suspicion of CGD, and genetic testing later confirmed an autosomal recessive mutation in

NCF1. Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation was also identified in the liver biopsy of patient 2. Bacterial hepatic abscesses are a hallmark of CGD (

Chusid 1978;

Lublin et al. 2002;

Szekely et al. 2012), and have been reported in approximately 30% of patients (largely associated with

Staphylococcus aureus infection) (

Winkelstein et al. 2000). Microabscesses in the liver and spleen can also develop as a result of fungemia. Due to the rarity of hepatic abscesses in young children (

Lublin et al. 2002), its detection should trigger investigation of CGD as a potential cause.

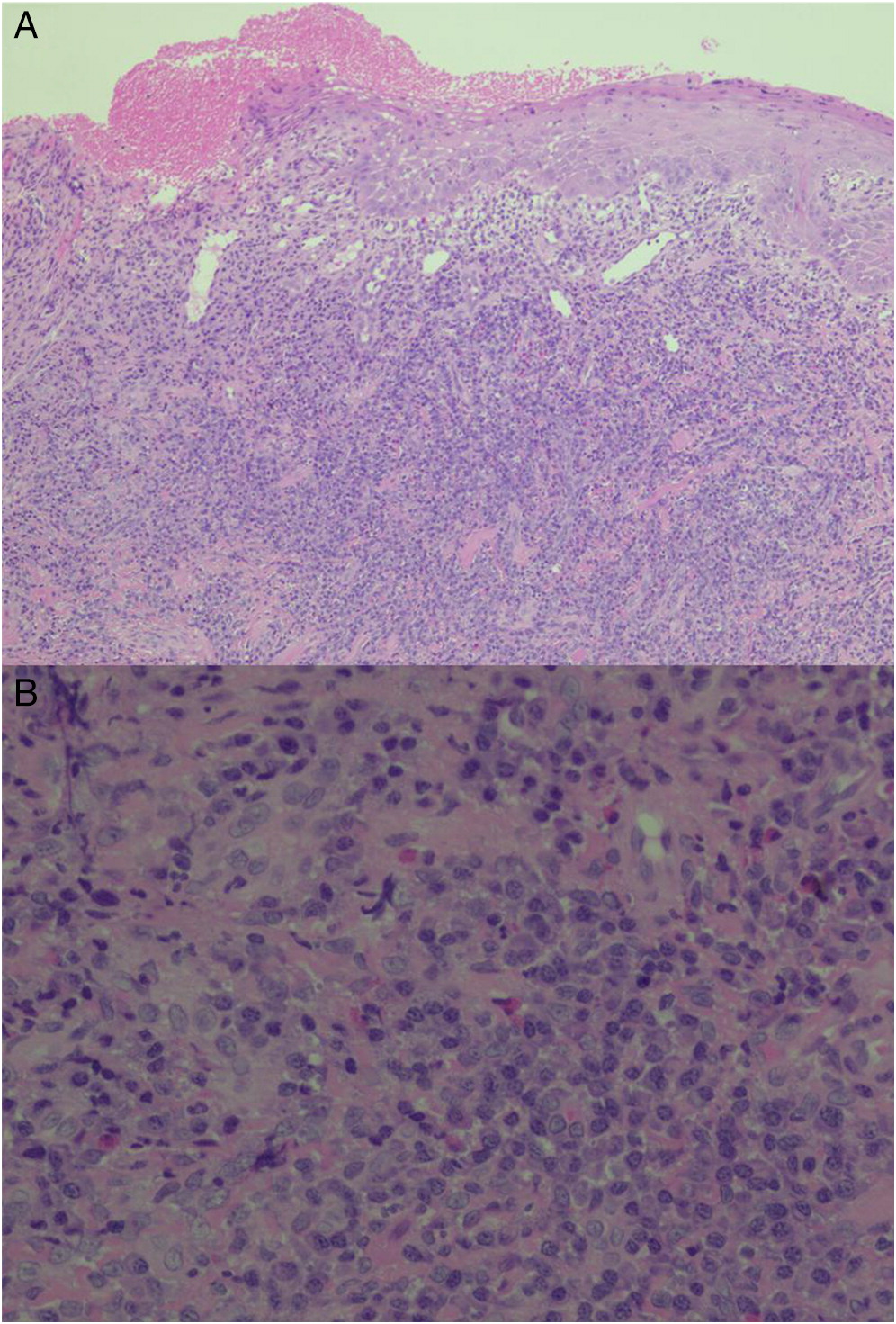

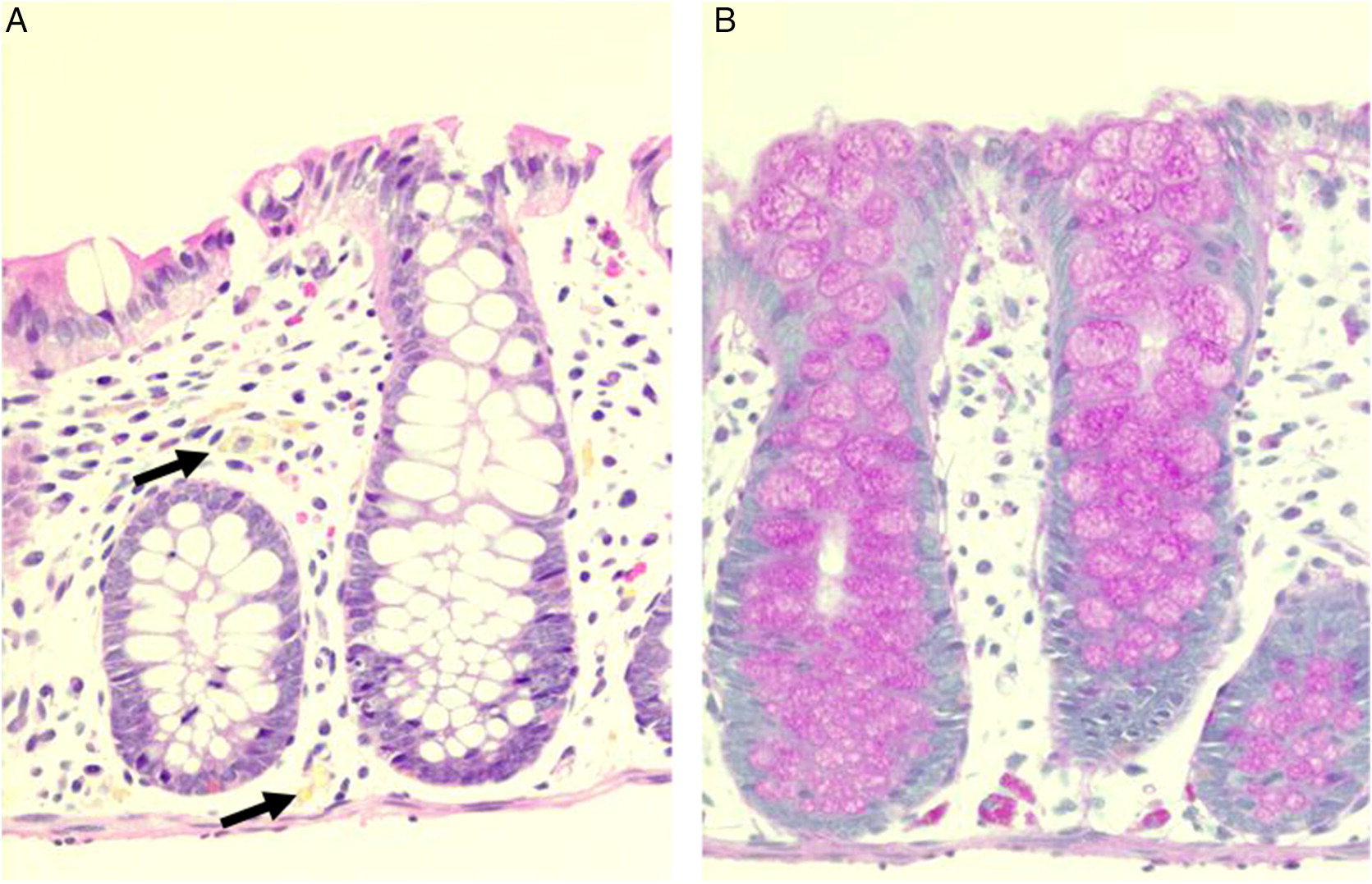

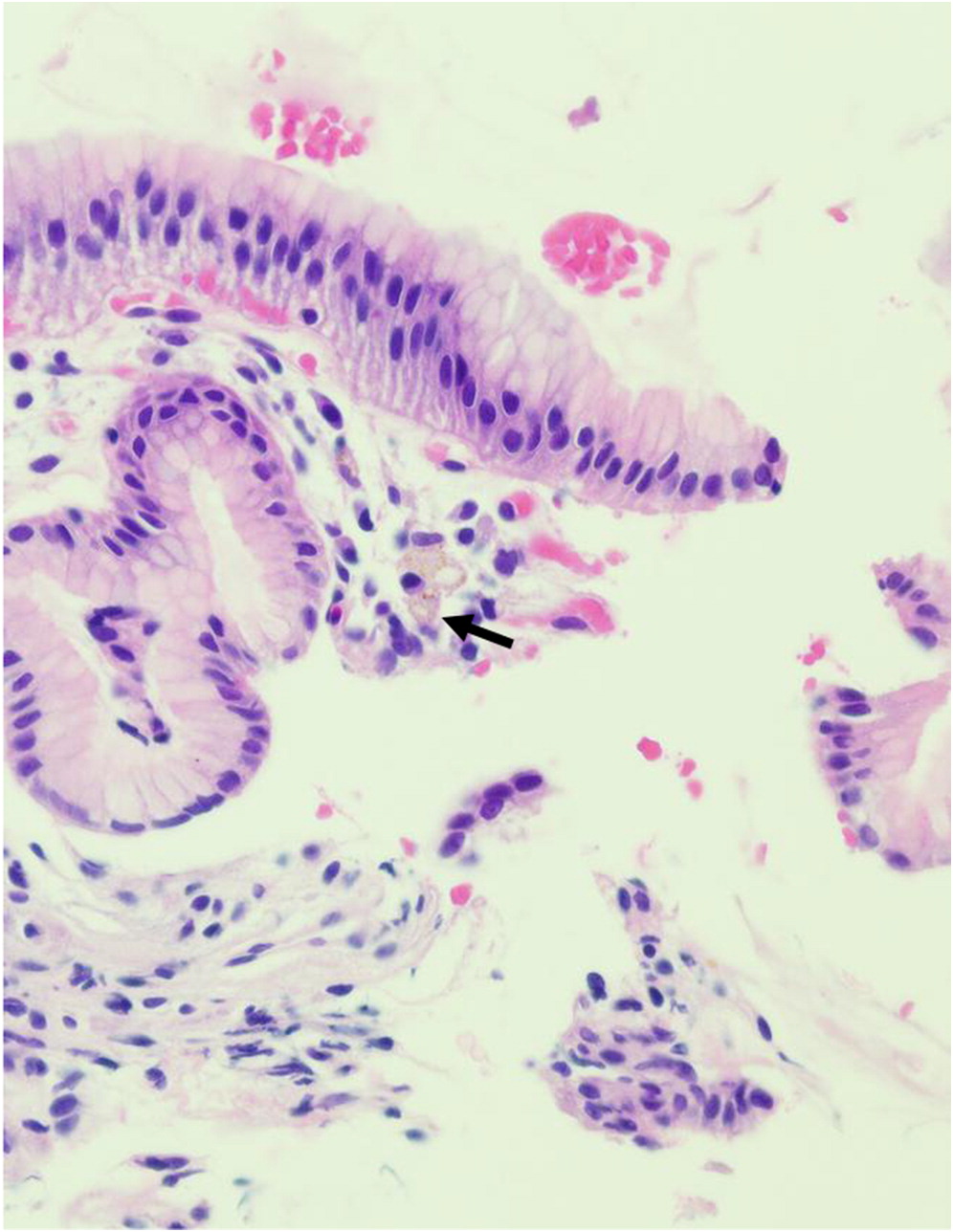

Manifestations of CGD in the GI tract can mimic other inflammatory bowel diseases (

Rieber et al. 2012), affecting up to 50% of CGD patients and may precede diagnosis of the disease (

Winkelstein et al. 2000;

van den Berg et al. 2009). Clinical symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and failure to thrive (

Marciano et al. 2004), and is often misdiagnosed as very early onset inflammatory bowel disease in young children (

Harris and Boles 1973). Histopathological evaluation may reveal inflammatory lesions anywhere along the length of the GI tract, from the mouth to the anus, with or without infectious etiology (

Huang et al. 2006;

Towbin and Chaves 2010). Often, biopsies reveal granuloma formation, nuclear debris, as well as the presence of pigmented macrophages in the lamina propria. Localization of pigmented macrophages in the deep layers of tissue, from the lamina propria through to the mucosa, submucosa and muscularis propria, has also been reported in GI biopsies of affected patients (

Alimchandani et al. 2013). In addition, eosinophilia and microscopic eosinophilic crypt abscesses are usually detected in the absence of acute, neutrophilic inflammation. In patient 3, eosinophilic crypt abscesses and PAS positive macrophages were identified in the duodenum and rectum, respectively. His vomiting was explained by gastric outlet obstruction—part of a spectrum of manifestations of CGD which include colitis, dysmotility, abscesses, strictures, and oral ulcers (

Marciano et al. 2004;

Damen et al. 2010). In patient 4, scattered pigmented macrophages were identified in biopsies of the stomach and colon, collected during upper and lower GI endoscopy.

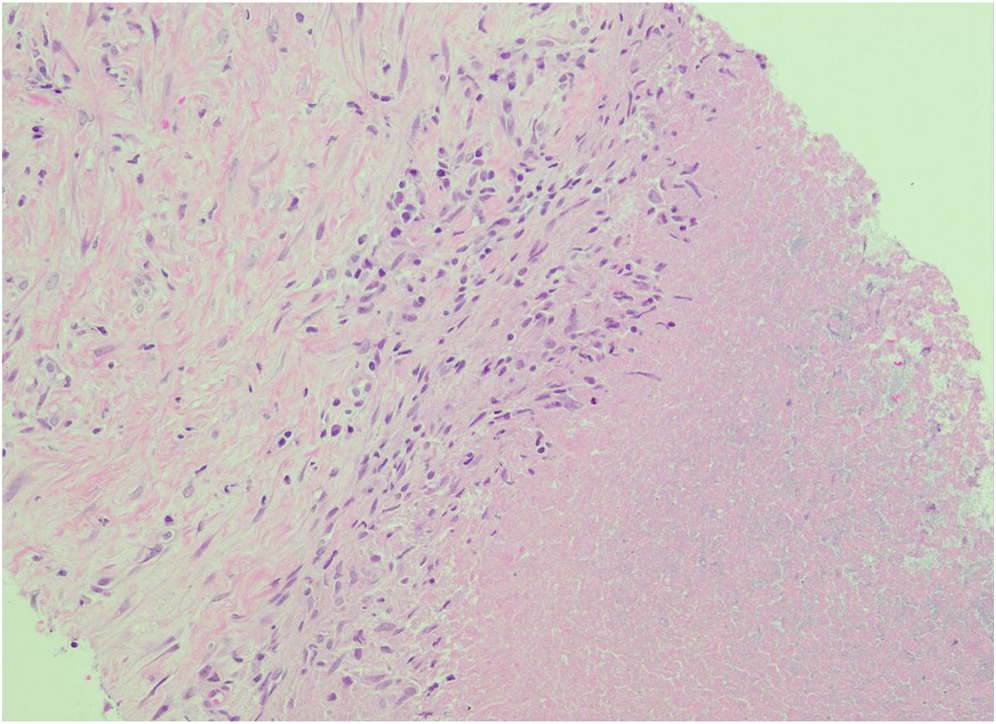

Involvement of the skin has been reported in up to 65% of CGD patients (

Dohil et al. 1997), and include inflammatory lesions associated with aspergillosis or without infectious etiology, cutaneous granulomas, and on some occasions the presence of pigmented macrophages (

Levine et al. 2005). The inflammatory process/abscess identified in the foot and thigh of patient 5 is an uncommon finding and rarely reported.

In summary, we show that histopathology in combination with careful assessment of patient history, radiography, and phagocyte cell function analysis, can raise strong suspicion of CGD.