Introduction

Autoinflammatory diseases are a genetically heterogeneous group of conditions characterized by excessive activation of the innate immune system, and are distinguished from autoimmunity by the absence of autoantibodies and non-dependence on antigens (

McGonagle and McDermott 2006;

Martorana et al. 2017;

Nigrovic et al. 2020). Aberrations in innate immune function, such as those involved in the detection of pathogens and (or) downstream signalling pathways that relay these responses, form the basis of the 5 major categories of autoinflammatory diseases. These include (

i) inflammasomopathies (defects in multi-protein inflammasomes responsible for caspase-1-dependent IL-1β production), (

ii) interferonopathies (defects in intracellular DNA sensors or counteracting nucleases leading to constitutive production of type I interferons), (

iii) unfolded protein/cellular stress response syndromes (defects in handling of misfolded proteins resulting in activation of immune cascades, such as inflammasomes and interferon pathways), (

iv) relopathies (defects in regulators of NF-κB-activity leading to hyperactivation), and (

v) uncategorized (

Rood and Behrens 2022). The clinical features frequently overlap and may include fever, rash, serositis, meningitis, gastrointestinal manifestations, and arthritis. A diagnosis is made based on correlation of symptoms against those of known autoinflammatory diseases (

Tunca and Ozdogan 2005) and may be supported by genetic analysis (

Simon et al. 2006).

With the advancement of genetic sequencing techniques, this field has grown exponentially with now recognized monogenic and polygenic origins (

Pathak et al. 2017). Manifestations of digenic inheritance arising from the

MEFV gene, causing the most common form of autoinflammatory disease – familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), alongside the

NOD2 gene, have been previously noted (

Yao et al. 2019).

The

MEFV gene is located on chromosome 16 and encodes pyrin, a 781-amino acid protein that serves as a cytosolic sensor of bacterial-induced Rho GTPase inactivation. Pyrin is expressed in the cytoplasm of cells from myeloid lineages, synovial fibroblasts, and dendritic cells. Engagement and assembly of the pyrin inflammasome activates caspase-1, resulting in proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β and IL-18 production, and pyroptosis (inflammatory cell death) (

Nigrovic et al. 2020). Autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant mutations in

MEFV, causing excess activation of the pyrin inflammasome, can result in the clinical phenotype of FMF (OMIM # 134610, #249100) (

Booty et al. 2009;

Chae et al. 2011;

Nigrovic et al. 2020;

Tunca and Ozdogan 2005). While FMF can affect any ethnic group, the prevalence is estimated to be as high as 1:200 in certain Mediterranean populations.

Presentation of FMF usually occurs during childhood with major criteria of recurrent episodes of fever with serositis, amyloidosis and (or) favorable response to colchicine, and minor criteria encompassing recurrent fever, erysipelas-like erythema, or a first degree relative with FMF. Other features include abdominal and (or) chest pain, monoarticular arthritis, neutrophilia, elevated inflammatory markers, and amyloidosis commonly involving the kidneys.

A role for

NOD2 as a gene modifier for FMF, causing more severe disease, has been suggested (

Berkun et al. 2012). The

NOD2 gene is located on chromosome 16 and encodes NOD2 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2), a member of the intracellular NOD-like receptor (NLR) family of pattern recognition receptors (PRR). This innate sensor detects bacterial motifs (peptidoglycan) and promotes bacterial clearance through activation of the NF-kB pathway and induction of autophagy (

Caruso et al. 2014). NOD2 is expressed primarily in monocytes but is also present in macrophages, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, epithelial and endothelial cells, as well as intestinal Paneth cells.

Here, we report the complex medical and family history of an adult male who presented at an early age with autoinflammation and immunodeficiency. Targeted panel sequencing identified 3 missense mutations, 2 in MEFV and 1 in NOD2.

Case presentation

Our patient is currently a 68-year-old male of European descent who was referred to our clinic at age 64 after a remarkable and complex medical history since childhood.

Family history

The patient’s family history is notable for malignancy with prostate, bowel, and laryngeal cancer in his father, bowel cancer in his paternal grandmother, and breast cancer in his paternal aunt. He had a sister who died before the age of 1 year from an unknown cause, and his brother has a history of viral cardiomyopathy. His mother had coronary artery disease, Sick Sinus Syndrome and recurrent episodes of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. His father, in addition to malignancy, also had Sick Sinus Syndrome. His daughter has hypothyroidism and his son has Crohn’s disease.

Infections

Our patient presented with repeated tonsillitis from 4 years of age and recurrent sinus infections from 10 years of age, which required surgery and repeated admission for intravenous antibiotics even through to adulthood. At age 7 years, he had right ulnar osteomyelitis requiring surgical management and plate insertion during early adulthood. Other infections included recurrent viral infections, Herpes Zoster, and recurrent warts since the age of 40 years. At 46 years of age, he was admitted for intravenous antibiotic therapy due to prostatitis and septicemia. He also had multiple episodes of cellulitis since childhood, mainly on his arms and hands with increased frequency during the last few of years, including repeated cyst sebaceous infection. Biopsy confirmed dermal scarring reaction with abscess formation including prominent foreign body type granulomatous reaction. Another skin lesion of interest was a perianal condyloma found on pathology.

Gastroenterology

He suffered from recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloating since early adulthood. After several evaluations during his 50´s, he was found to have bowel polyps, adenomas, and lymphoid hyperplasia. A liver biopsy showed mild steatosis and minimal fibrosis. At age 54 years, he was diagnosed with sclerosing mesenteritis and is currently treated with colchicine, tamoxifen, steroids, and methotrexate. In his late 60’s, he developed pancreatitis due to a pseudocyst, complicated with acute renal failure. No hepatosplenomegaly is noted.

Autoinflammation and autoimmunity

At the age of 44 years, autoimmune thyroiditis and hypothyroidism were identified. He also experienced triphasic Raynaud’s phenomenon, which worsened during winter. By his late adulthood he was diagnosed with iritis, a form of uveitis, which concurred with a Herpes Zoster infection. By 63 years of age, he had 7 hospitalizations including 1 for possible viral encephalitis, mitochondrial disease, or cryoglobulinemia. He has cervical osteoarthritis affecting his vertebral column which is managed by steroids.

Cardiovascular

During his late 50’s, our patient was diagnosed with mild aortic root dilatation and left ventricular hypertrophy with hypertension, and in his early 60’s with premature ventricular contractions, bigeminy, trigeminy, palpitations, and bundle branch block. He developed severe mitral valve regurgitation at 61 years old. During that time he presented with an unprovoked deep vein thrombosis, and remains on long-term treatment with warfarin. On recent evaluation, a grade 3/6 pan-systolic murmur and trigeminal arrhythmia were noted.

Malignancy

Following 10 years of severe prostatitis, he was diagnosed at age 56 years with prostate cancer and underwent radical prostatectomy. He has since had 2 normal bone marrow aspirates with no signs of lymphoproliferative disorders.

Neurologic

At 52 years of age, concerns about transient ischemic attack were raised after sudden unexplained and non-specific weakness of his right upper extremity. MRI showed small chronic left cerebellar infarct and chronic small vessel ischemic background changes. Upon psychiatric evaluation, cortical problems, decreased performance, and concentration were noted.

Respiratory

The patient has suffered from severe obstructive sleep apnea since age 60 years. A CT scan of the chest revealed 2 lung nodules with some atypical fibrosis.

Physical evaluation

The patient has facial plethora and flush, bilateral supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, and his ear, nose, and throat demonstrate edematous nasal turbinate. The skin on his upper back has some round scaly, shiny lesions of 2-3mms in diameter, which the patient describes as initially appearing as a red bump, then turning white at the centre and becoming scaly. He has multiple telangiectasias on his arms and back as well as a baseline erythroderma.

Immune evaluation

Immune investigations performed in the context of prolonged use of steroids showed slightly low immunoglobulins G and M, with normal Immunoglobulin A (IgG: 5.21 g/L, IgA 1.4 g/L, IgM: 0.37 g/L) while specific antibody titers against mumps, measles, rubella, tetanus, and varicella were protective (

Table 1). Lymphocyte immunophenotyping demonstrated low B cell numbers of 43 cells/μL (normal: 100–500 cells/μL), low CD8+ T cells (CD3+CD8+: 69 cells/μL, normal: 200–900 cells/μL; CD3+CD4+: 435 cells/μL, normal: 300–1400 cells/μL) with a significant predominance of CD4+ over CD8+ T cells, at a ratio of 6.3 (normal: 1–3.6). Lymphocyte proliferation to the mitogen phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was normal, with a stimulation index of 1649. Autoantibodies were weakly positive for anti-Ro 52 and anti-SCL 70/topoisomerase. He receives IVIG based on borderline low IgG and IgM levels.

Genetic investigations

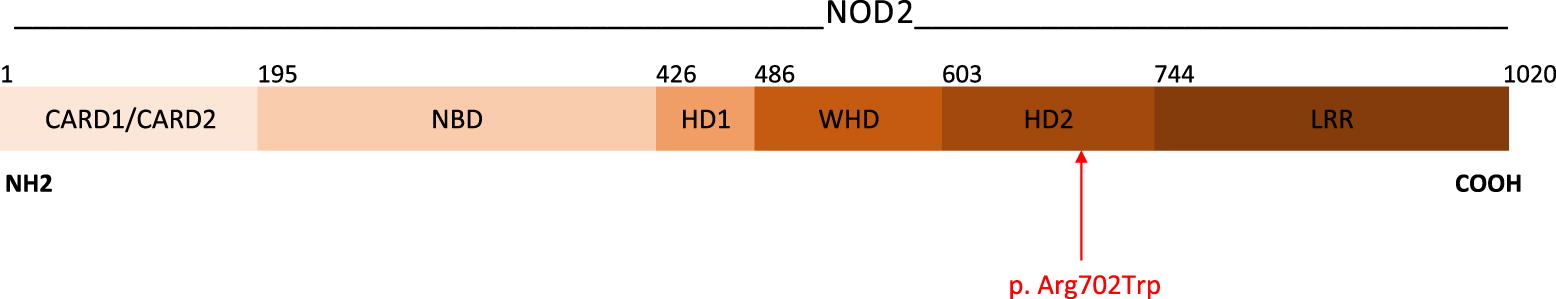

A 17-gene autoinflammatory disease panel detected 3 variants of uncertain significance. A heterozygous variant in the

NOD2 gene (NM_022162.1)(

Figure 1), resulting from the substitution of an arginine residue with tryptophan at position 702, NOD2:c.2104C>T (p.Arg702Trp), was reported. While there is no consensus regarding the pathogenicity of this variant (Sift, Polyphen, Mutations Taster), it has previously been reported in patients with features of Yao Syndrome (

Yao et al. 2011;

Yao and Shen 2017;

Chapman et al. 2009) as well as Crohn’s disease (

Yazdanyar et al. 2009;

Chapman et al. 2009;

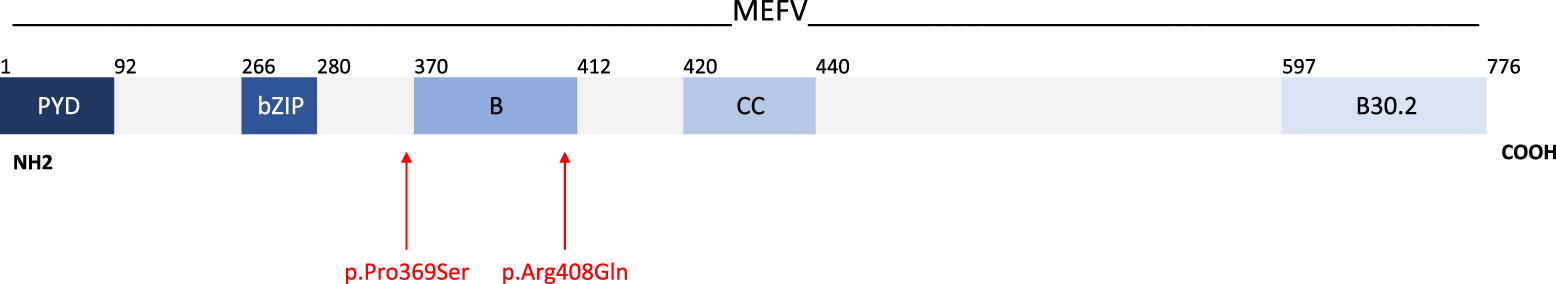

Christodoulou et al. 2013). Additionally, 2 heterozygous variants in

MEFV gene (NM_000243.2)(

Figure 2) were noted, 1 resulting in the substitution of proline with serine in the position 369, MEFV:c.1105C>T (p.Pro369Ser), with no consensus regarding its pathogenicity (

Aksentijevich et al. 1999;

Hannan et al. 2012;

Migita et al. 2014), and the other resulting in the substitution of an arginine with a glutamine residue at position 408, MEFV:c.1223G>A (p.Arg408Gln), predicted to be benign (

Cazeneuve et al. 1999;

Ryan et al. 2010;

Hannan et al. 2012;

Migita et al. 2014). Both MEFV variants have a high frequency in control populations and been documented as low penetrance mutations in cases of FMF. The combination of these 2 MEFV gene variants have been reported in multiple individuals with FMF with a highly variable phenotype (

Cazeneuve et al. 1999;

Ryan et al. 2010).

Discussion

Here, we describe a patient who presented with 3 heterozygous variants of uncertain significance, 2 in the MEFV gene (associated with autoinflammatory disease) and 1 in the NOD2 gene (associated with autoinflammatory disease and immunodeficiency).

The diagnosis of FMF in adults is based on the fulfillment of either 2 or more major criteria of recurrent episodes of fever with serositis, amyloidosis, favorable response to colchicine, or 1 major and 2 minor criteria of recurrent fever, erysipelas-like erythema, or a first degree relative with FMF. Our patient’s clinical phenotype did not fit the classical phenotype of FMF, given the absence of symptoms listed above. Yet, a case series by Ryan and colleagues (

Ryan et al. 2010) previously reported the heterogenous and atypical FMF phenotype of a cohort of patients harbouring heterozygous

MEFV mutations, including the identical 2 mutations that were present in our patient, c.1105C>T (p.Pro369Ser) and c.1223G>A (p.Arg408Gln). Both are located within exon 3 of

MEFV encoding the B-box zinc finger domain (

Figure 2), a region that negatively regulates activation of the pyrin inflammasome. While 17 of 22 patients did not meet the diagnostic criteria for FMF, a clustering of symptoms was reported, including 1 whose symptoms included panuveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, lethargy, and intermittent fever. Lymphadenopathy and lack of response to colchicine, the mainstay treatment for FMF, were noted in a number of patients. These symptoms overlap with our patient’s presentation (with the exception of fever) and may partially explain his complex phenotype.

The coexistence of

MEFV and

NOD2 genetic variants, both located in chromosome 16, is relatively common and is marked by overlapping clinical features, variable penetrance, leading to phenotypic heterogeneity and therapeutic variability (

Yao et al. 2019). Case reports and cohorts of such combinations have demonstrated a high association with Crohn’s disease among patients with FMF (

Berkun et al. 2012). The NOD2 mutation present in our patient, c.2104C>T (p.Arg702Trp), is considered a risk factor for Crohn’s disease, and has also been described in patients with Yao Syndrome, an autoinflammatory disease characterized by periodic fever, dermatitis, arthritis, swelling of the distal extremities, gastrointestinal and sicca-like symptoms, and serositis (

Yao and Shen, 2017;

Yao et al. 2019). Notably, the phenotype of our patient was not consistent with either Crohn’s disease or Yao syndrome, particularly given the lack of fever — a major criteria for Yao Syndrome. Moreover, although there is often clinical overlap between Yao Syndrome and FMF, with some case reports suggesting that patients may present features of both autoinflammatory diseases when variants in both genes are present, this has not been reported for the combination of variants identified in our patient (

Yao et al. 2021).

NOD2 is also responsible for Blau Syndrome and Early Onset Sarcoidosis, the hereditary and sporadic forms (respectively) of a rare autoinflammatory disease caused by gain-of-function mutations in

NOD2. Affected individuals present with non-caseating granulomatous arthritis, uveitis, and dermatitis (

Tangye et al. 2022). Our patient’s symptoms are consistent with Blau syndrome, and in combination with his underlying

MEFV mutations, may help to explain his complex presentation. Notably, the c.2104C>T (p.Arg702Trp) variant in

NOD2 has not yet been reported in individuals with Blau Syndrome. Still, some features are not completely explained by his genetic work-up, such as malignancy, and further studies may be needed to rule out an association.

In summary, we describe a patient with a complex, longstanding, and early onset autoinflammatory disease. Genetic analysis identified 3 variants of uncertain significance in the MEFV and NOD2 genes.