Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide-responsive beige-like anchor (LRBA) is an intracellular protein that prevents the trafficking and degradation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4), an essential immune checkpoint molecule which dampens T cell-mediated responses and regulates immune self-tolerance. CTLA4 impairs the classic CD28 signaling pathway by binding the costimulatory ligands CD80 and CD86, located on antigen presenting cells, leading to ligand internalization and degradation. Given the linked biology of LRBA and CTLA4, absence of either molecules result in uncontrolled T cell activation, differentiation, and effector responses (

Lo et al. 2015).

LRBA deficiency was first reported in 2012 in 4 consanguineous families with humoral immunodeficiency and features of autoimmunity (

Lopez-Herrera et al. 2012). The clinical presentation of LRBA deficiency has since expanded from the early descriptions of recurrent infections, autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, chronic diarrhea, hypogammaglobulinemia and cytopenia, to include common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS)-like phenotypes (

Cagdas et al. 2019) (

Kostel Bal et al. 2017). Patients with ALPS-like phenotype presented with symptoms of organomegaly, lymphoproliferation, and elevated double negative T cells.

To date, there have been scarce reports of atypical presentations of LRBA deficiency, such as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (

Ren et al. 2021) and neurological manifestations. HLH is a rare and life-threatening syndrome characterized by uncontrolled immune activation and tissue destruction. The diagnostic criteria for HLH include fever, splenomegaly, bicytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia with or without hypofibrinogenemia, haemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes or cerebrospinal fluid, reduced natural killer (NK) cell activity, ferritin >500 ng/mL, and soluble CD25 >2400 U/mL. Patients must fulfil at least 5/8 criteria to reach a diagnosis of HLH (

Henter et al. 2007). Notably, some patients may present with atypical features, including neurological symptoms (ataxia, seizures).

Herein, we report the clinical course of a young boy who first presented at age 15 months with fever, bicytopenia, encephalopathy, and seizures. Subsequent whole exome sequencing (WES) identified genetic aberrations in the LRBA gene, encoding LRBA.

Results

Clinical features

Our male patient was born at term with no significant antenatal and postnatal complications. He was well during his first year of life, and thriving with normal development. At 15 months of age, he presented with prodrome of fever and reduced appetite for 3 days and was managed symptomatically at home. On day 3 of illness, he developed acute onset flaccid tone with eye deviation to the right and jerking movement of the distal limbs, which was treated with midazolam. He was subsequently admitted to the local hospital for febrile seizure. Four days later, he had seizure recurrence with a generalized tonic-clonic seizure with eye deviation to the left, which was sustained for 30 minutes. He had significantly decreased level of consciousness after the event and was encephalopathic.

His parents are both of Pakistani descent and consanguineous (first cousins), and he has 3 healthy older sisters. There is no significant family history of recurrent infection, metabolic, or genetic disease. His mother is healthy and father reports underlying congenital absence of vas deferens.

Our patient was referred to SickKids Hospital for further evaluation and management and subsequently admitted to ICU. Clinical examination revealed a thriving child with no dysmorphic features. There was no lymphadenopathy, and cardiovascular and respiratory examination was normal. Abdominal examination revealed an enlarged liver 5 cm below the costal margin, however, there was no splenomegaly. Neurological examination revealed abnormal posturing, increased tone, and brisk reflexes.

Laboratory evaluation

Laboratory evaluations (

Table 1) revealed leukopenia and anaemia with thrombocytosis. His absolute neutrophil count was low. Liver enzymes alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) were elevated. Nasopharyngeal swab for viruses were negative, including for Influenza. Other infectious work-up which included serology for Bartonella, West Nile Virus/Flavivirus, Dengue, Parvo, Lyme, syphilis, Mycoplasma, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) were all negative except for human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6). Lumbar puncture results revealed white blood cells (WBC) at 1 × 10

6/L, red blood cells (RBC) at 2 × 10

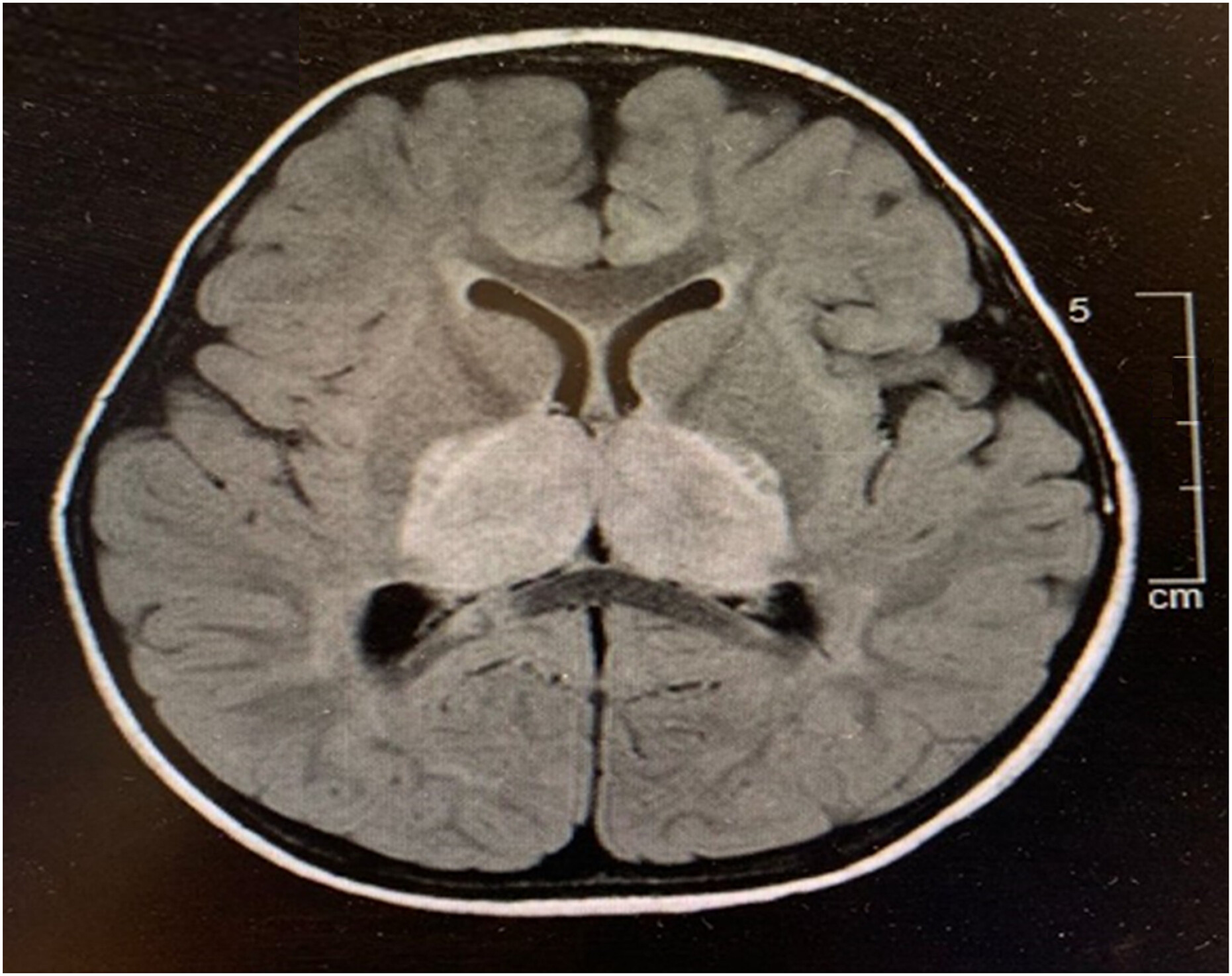

6/L, protein at 1.39 g/L, and glucose at 3.9 mmol/L. Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF)cultures were negative. CSF PCR was negative for herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Mycoplasma, but positive for HHV6. He was evaluated for HLH and had elevated ferritin and triglyceride and low fibrinogen, however, he did not meet the diagnostic criteria for HLH. His immunoglobulin levels were normal. Bone marrow examination was inconclusive. Natural killer (NK) cell degranulation and CD56/perforin were within normal range. Soluble CD25 and CD163 were normal. Electroencephalogram and magnetic reasonance imaging (MRI) results (

Figure 1,

Figure 2) were suggestive of acute necrotizing encephalopathy. He received high dose pulse IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg for 5 days) and plasmapheresis for 4-daily treatments. He responded to treatment with marked neurological improvement and upon discharge had minimal neurological deficit. He continued to show improvement in his neurological parameters during subsequent follow-up.

Progression of illness

At 36 months of age, our patient presented to a local hospital in Pakistan with similar symptoms. He developed high grade fever, lethargy, and declining loss of consciousness. He subsequently developed severe encephalopathy, abnormal movements, and fixed dilated pupils. Blood investigations revealed elevated neutrophils, lactate, liver enzymes (ALT was 678 U/L), C-reactive protein, ferritin, and prolonged prothrombin time. Dengue serology was positive. Urgent computerized tomography (CT) scan of the brain was reported locally as having cerebral oedema and bilateral thalamic disease. He was unstable during his admission to the intensive care unit and lumbar puncture and MRI was contraindicated. He received IV immunoglobulins and high dose methylprednisolone therapy. Despite treatment, he succumbed to his illness.

Genetic testing

Initial genetic testing included targeted sequencing of the RANBP2 gene, which was returned negative. An autoinflammatory panel noted a variant of uncertain significance in the MEFV gene, however, this did not fit the clinical picture of our patient.

In the year following his death, the parents were re-referred to our complex immunology clinic for further evaluation of a possible primary immunodeficiency.

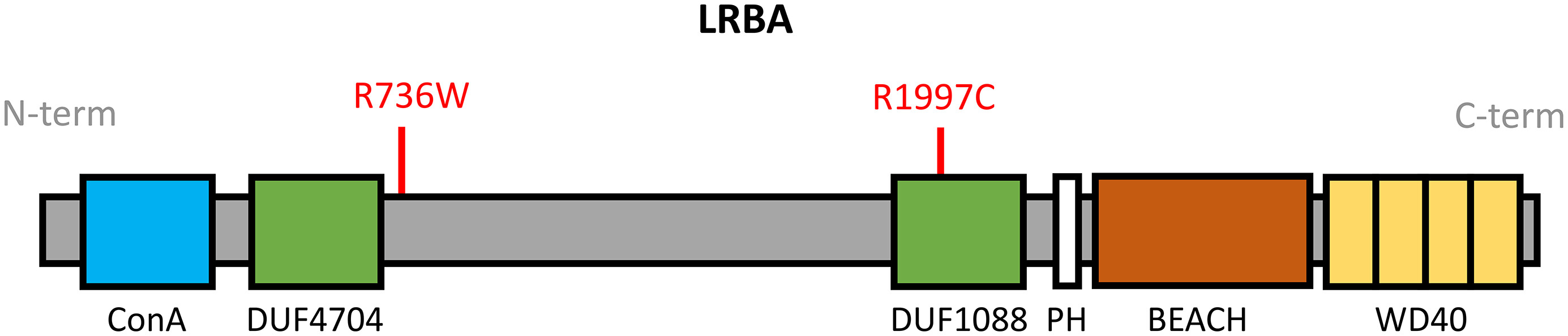

Research WES subsequently revealed a set of compound heterozygous missense mutations in the

LRBA gene (NM_001364905). The results were confirmed in a clinical laboratory (Primary Immunodeficiency Panel, Invitae). The first variant, c.2206A>T, targets exon 18 resulting in the substitution of arginine with threonine, p.R736W (

Figure 3), and has not been previously reported. It has an allele frequency of 0.0003099 in South Asians and 0 in other populations (gnomAD), and is predicted damaging by MutationAssessor (1.94). The second variant, c.5989C>T, targets exon 38 leading to substitution of cystine with threonine, p.R1997C (

Figure 3). It is predicted damaging according to SIFT (0.004), PP2 (0.966), and MutationAssessor (2.28), and has an allele frequency of 0.03778 (gnomAD).

Segregation analysis revealed the presence of the c.2206A>T (p.R736W) LRBA variant in the patient’s father, and the c.5989C>T (p.R1997C) variant in the patient’s mother.

Discussion

We describe here a patient with a set of compound heterozygous mutations in

LRBA with atypical presentation of recurrent HLH including CNS manifestations, who was initially diagnosed with acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood (ANEC). Our patient had features of ANEC (from EEG and MRI) and responded to initial treatment with IVIG and plasmapheresis with good neurological outcome. He was suspected to have an underlying monogenic mutation based on family history of consanguinity. Recurrent ANEC secondary to underlying

RANBP2 variants has previously been reported in patients with a positive family history or history of consanguinity (

Suri 2010) (

Neilson et al. 2009) (

Bashiri et al. 2020). The negative findings on

RANBP2 genetic sequencing prompted further genetic evaluation.

Research-based WES was essential for identifying the LRBA genetic aberrations in our patient and the interpretation will be an important consideration during future genetic counselling of his family members. Of the two variants described in this case study, c.2206A>T (p.R736W) is novel and previously unreported. The arginine residue at position 736 is perfectly conserved in vertebrates, moreover, the local region is highly conserved and in silico tools predict a functional impact. Regarding c.5989C>T (p.R1997C), the arginine residue at position 1997 is almost perfectly conserved in mammalians and vertebrates. The substitution with cysteine results in loss of a positive charge and marked shortening of the side chain. Thus, while the second mutation alone may not result in a significant clinical phenotype (as reflected by the higher frequency), when present in tandem, the combined impact of this set of compound heterozygous missense variants results in loss-of-function of LRBA. Our patient presented with an atypical phenotype of recurrent HLH with seizures and encephalopathy.

LRBA is a 2863 amino acid protein and contains multiple domains, including the Concanavalin A-like (ConA-like) domain, 2 domains of unknown function (DUF4704 and DUF1088), pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, beige and Chediak-Higashi (BEACH) domain, and WD40 repeat domains. The ConA-like domain located at the N-terminus binds to oligosaccharides and is involved in protein trafficking and sorting. The PH and BEACH domains form prominent grooves to recruit binding partners. Both the BEACH and WD40 repeat domains are involved in vesicle binding (

Figure 3).

Biallelic LRBA loss-of-function is one of the most common causes of common variable immunodeficiency. Deficiency of LRBA and thus diminished expression of the inhibitory checkpoint molecule CTLA4 on the surface of T reg cells leads to unrestrained immune responses and autoimmune features. Notably, given the linked pathways of CTLA4 and LRBA, there is significant clinical overlap between LRBA deficiency and CTLA4 haploinsufficiency. Patients harboring compound heterozygous mutations in

LRBA may present with a broader spectrum of manifestations, including autoimmune disease affecting multiple organs, chronic diarrhea, and organomegalies. Yao et al. describe a series of 5 cases with similar compound heterozygosity affecting

LRBA (

Yao et al. 2022). Interestingly, one of the cases was initially diagnosed with HLH due to fever, splenomegaly, elevated ferritin, low fibrinogen, hemophagocytosis, and hemopenia. He was successfully treated with HLH first-line chemotherapy. HLH-associated with a single heterozygous

LRBA variant has also been reported (

Ren et al. 2021) (

Mo et al. 2019). Our patient was worked up for HLH given his fever and bicytopenia, however, while ferritin and triglyceride levels were elevated and fibrinogen was low, other investigations were within normal range and thus he did not fulfil HLH criteria. Further, his ferritin and triglyceride subsequently returned to normal. During his second bout of illness, prior to his demise, he had elevated liver enzymes and ferritin. We postulate that our patient had recurrent HLH, precipitated by 2 viral infections - HHV6 and dengue.

Neurological manifestations including seizures, altered consciousness, facial palsy, or difficulty in swallowing/speech have previously been reported in patients with HLH, affecting up to 46% of cases (

Kim et al. 2012). In a large international cohort of 212 patients with LRBA deficiency, 12.3% were reported to have CNS effects, including seizure, neurodevelopment delay and demyelinating disorders (

Jamee et al. 2021). Further, a report of Iranian cohorts identified neurological manifestations in 23% of the patients (

Alkhairy et al. 2016), while Gamez-Diaz et al. reported that 5% of their patients with underlying LRBA deficiency presented with stroke (

Gamez-Diaz et al. 2016).

Unfortunately, due to his atypical presentation and rigidity of the HLH criteria, our patient remained without a diagnosis until comprehensive next generation sequencing in the form of WES was performed. Similarly, we recently reported the diagnostic odyssey of a patient with early signs of HLH and whom did not satisfy the criteria for many years (

Sham et al. 2022). It remains important for clinicians to consider atypical presentations of HLH as patients would benefit from specific medical therapy. In the case of LRBA deficiency, abatacept (a CTLA4-based fusion protein) has been shown to improve patient overall outcomes (

Kiykim et al. 2019).

In summary, this case helps to expand the known spectrum of disease associated with compound heterozygous mutations in LRBA. WES serves as a useful tool to diagnose and guide treatment in complex immunological diseases and thus should be considered in patients with atypical manifestations.