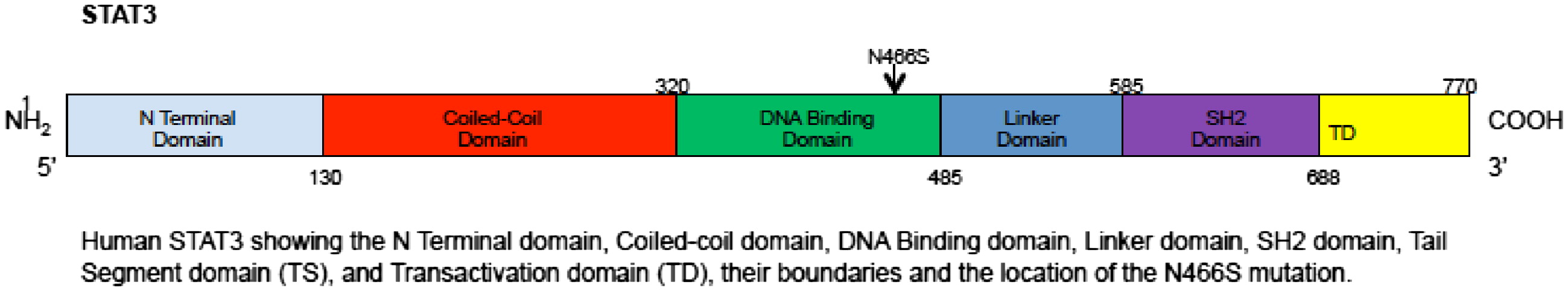

The characteristic infectious and noninfectious features of autosomal dominant

STAT3 mutation associated HIES are described in these 4 siblings and are demonstrated with supportive imaging. The pathogenesis of these features are felt to be related in part to defects in the secretion and signalling of a number of cytokines involved with the inflammatory response, as well as differentiation into effector cells such as Th17 which are important for the defense against bacterial and fungal infections (

Milner et al. 2008;

Heimall et al. 2010). As demonstrated in our patients,

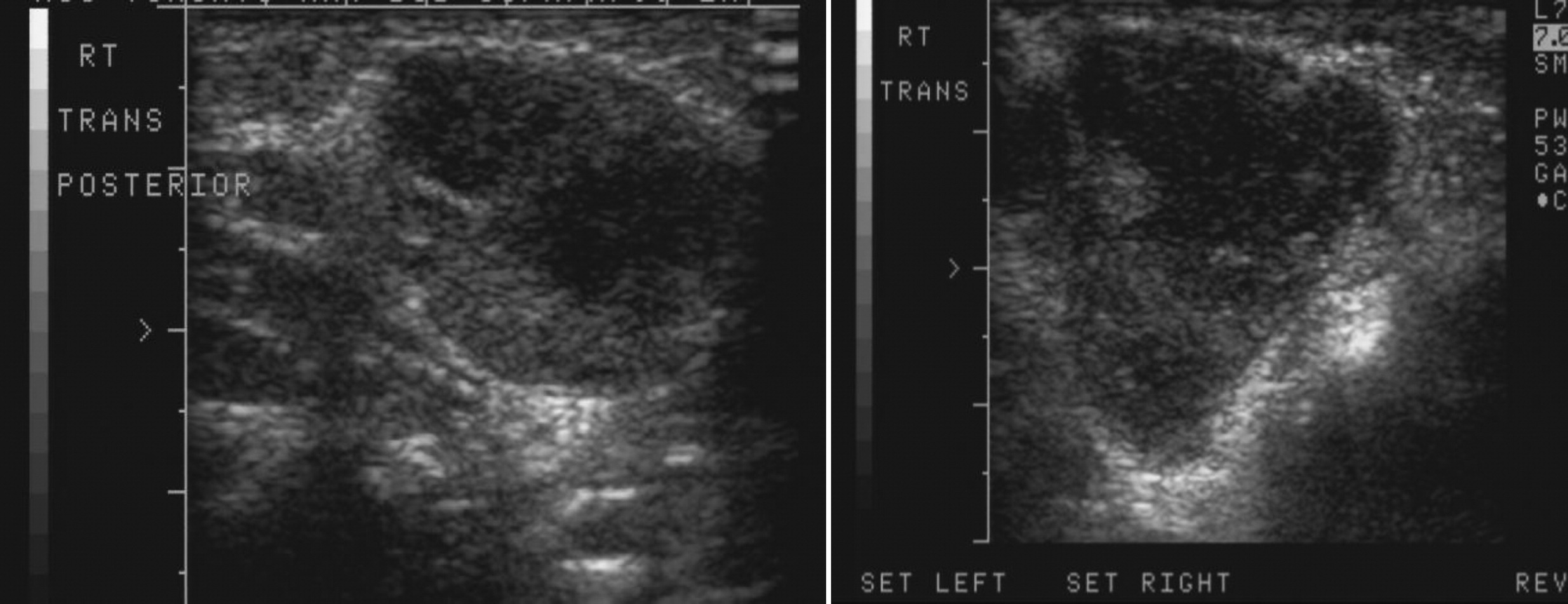

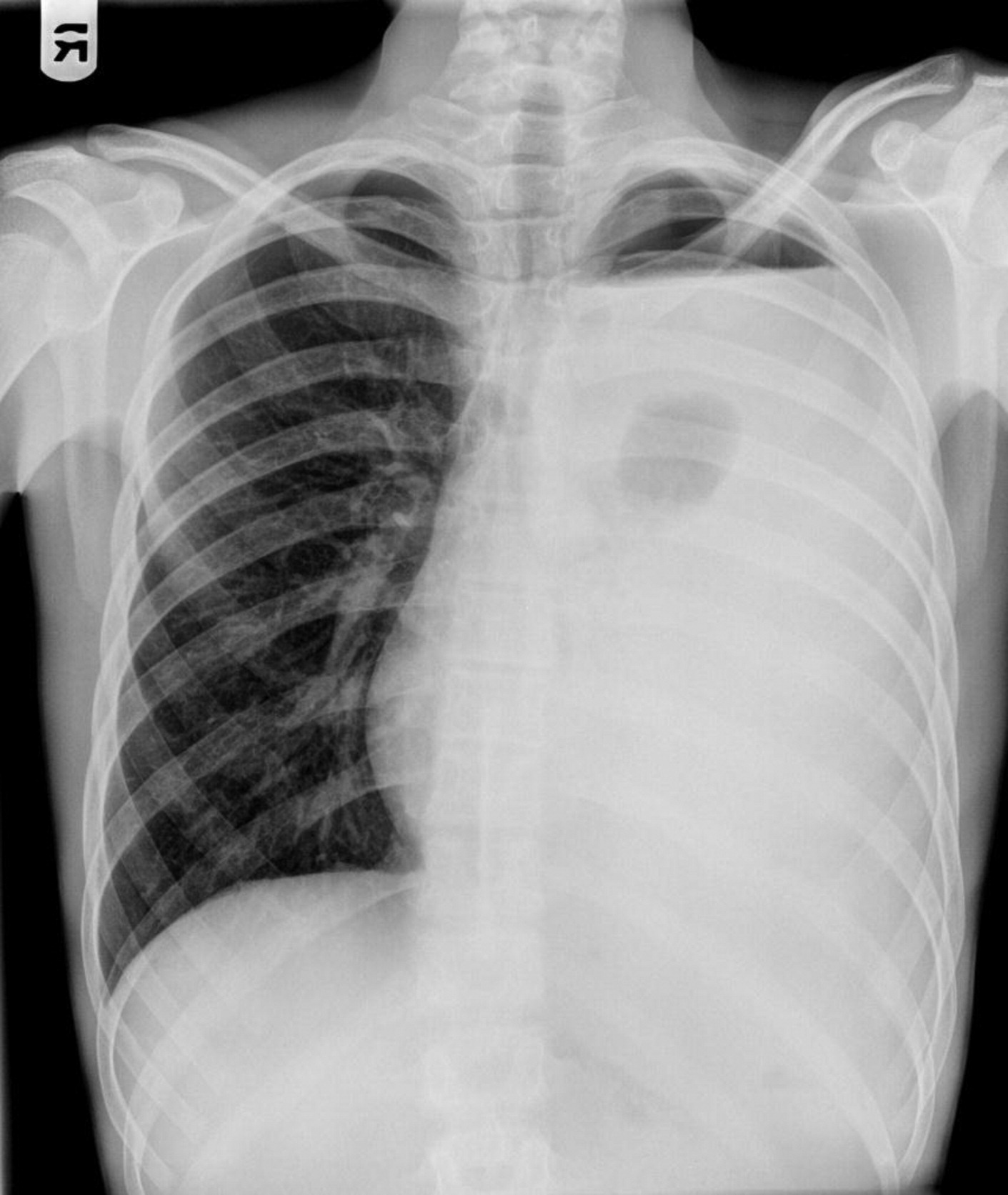

STAT3 mutations lead to susceptibility to sinopulmonary infections, especially due to

Staphylococcus aureus, which can progress to bronchiectasis, parenchymal lung damage, and formation of pneumatoceles (

Grimbacher et al. 1999a). Colonization of pneumatoceles with

Pseudomonas (

Grimbacher et al. 1999a),

Aspergillus (

Vihn et al. 2010) and nontuberculous

Mycobacterium (

Melia et al. 2009) are also reported.

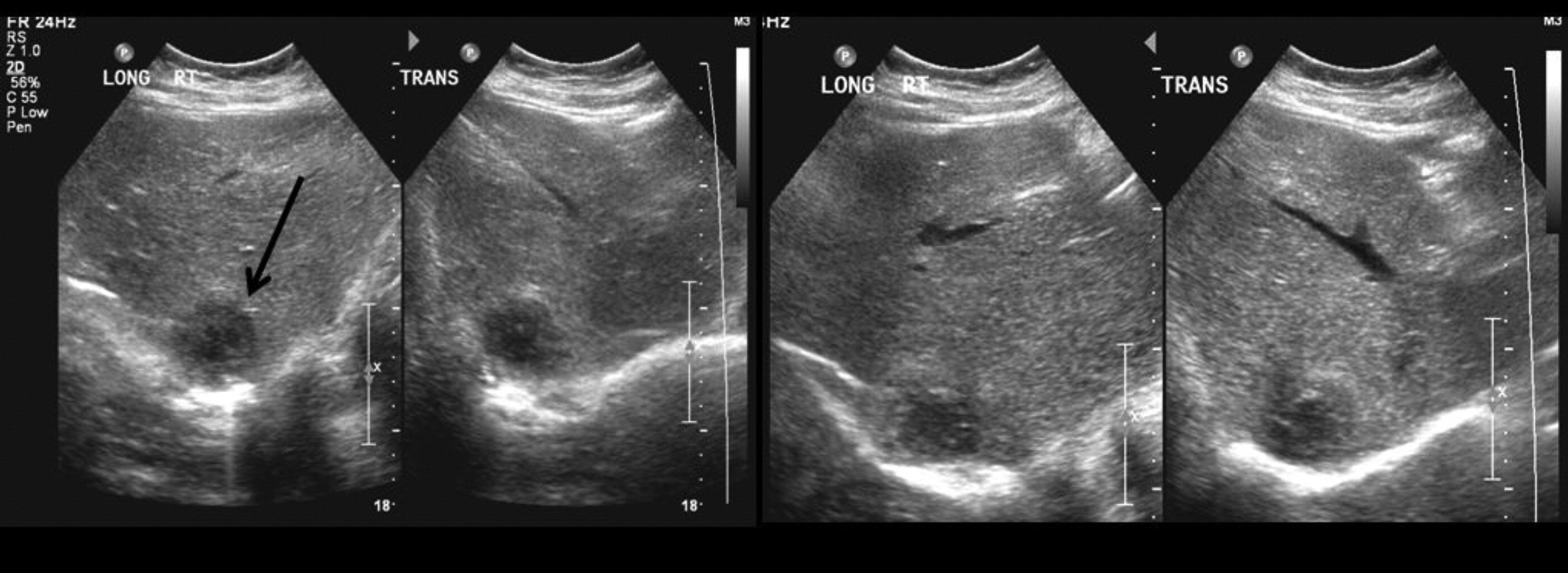

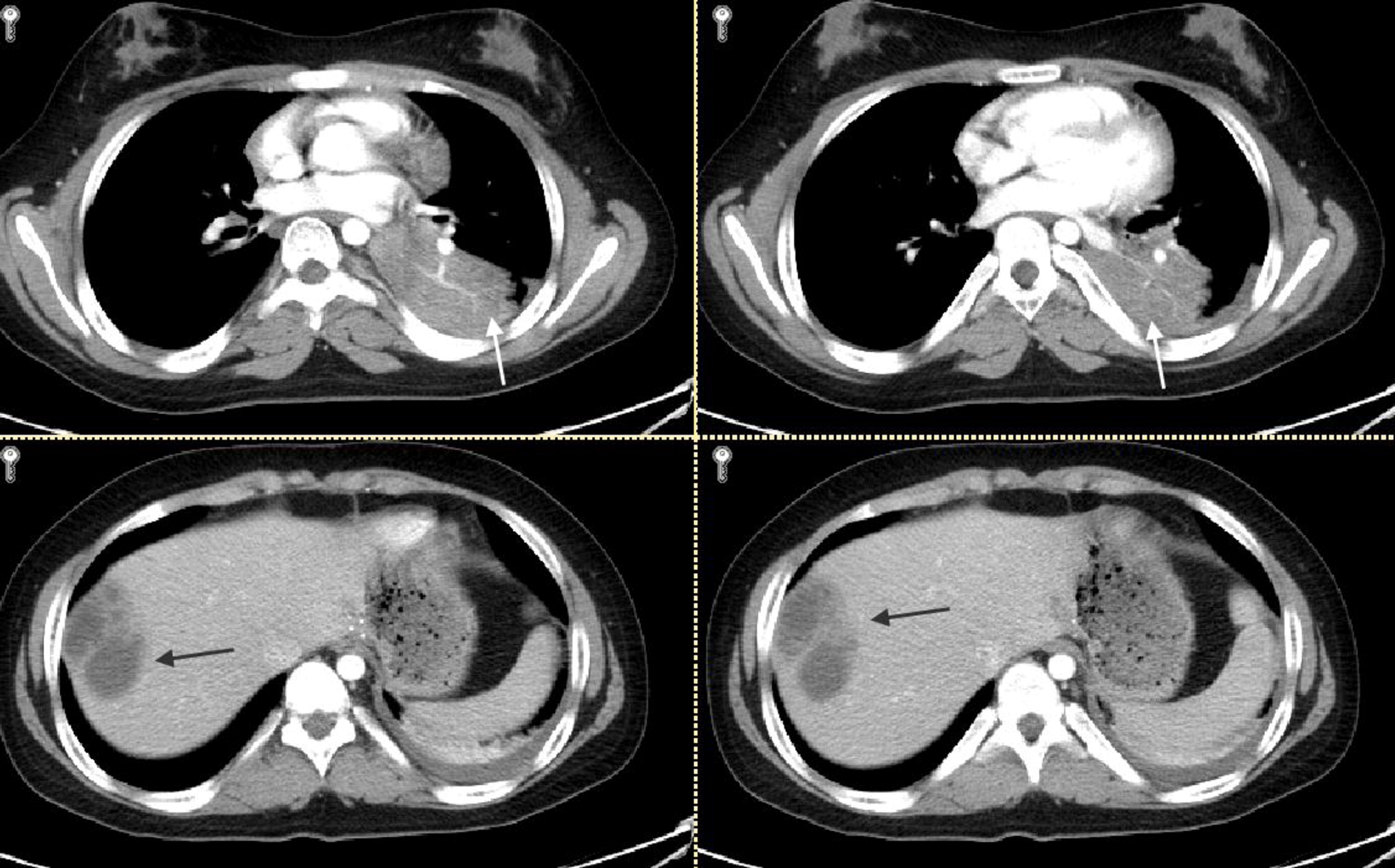

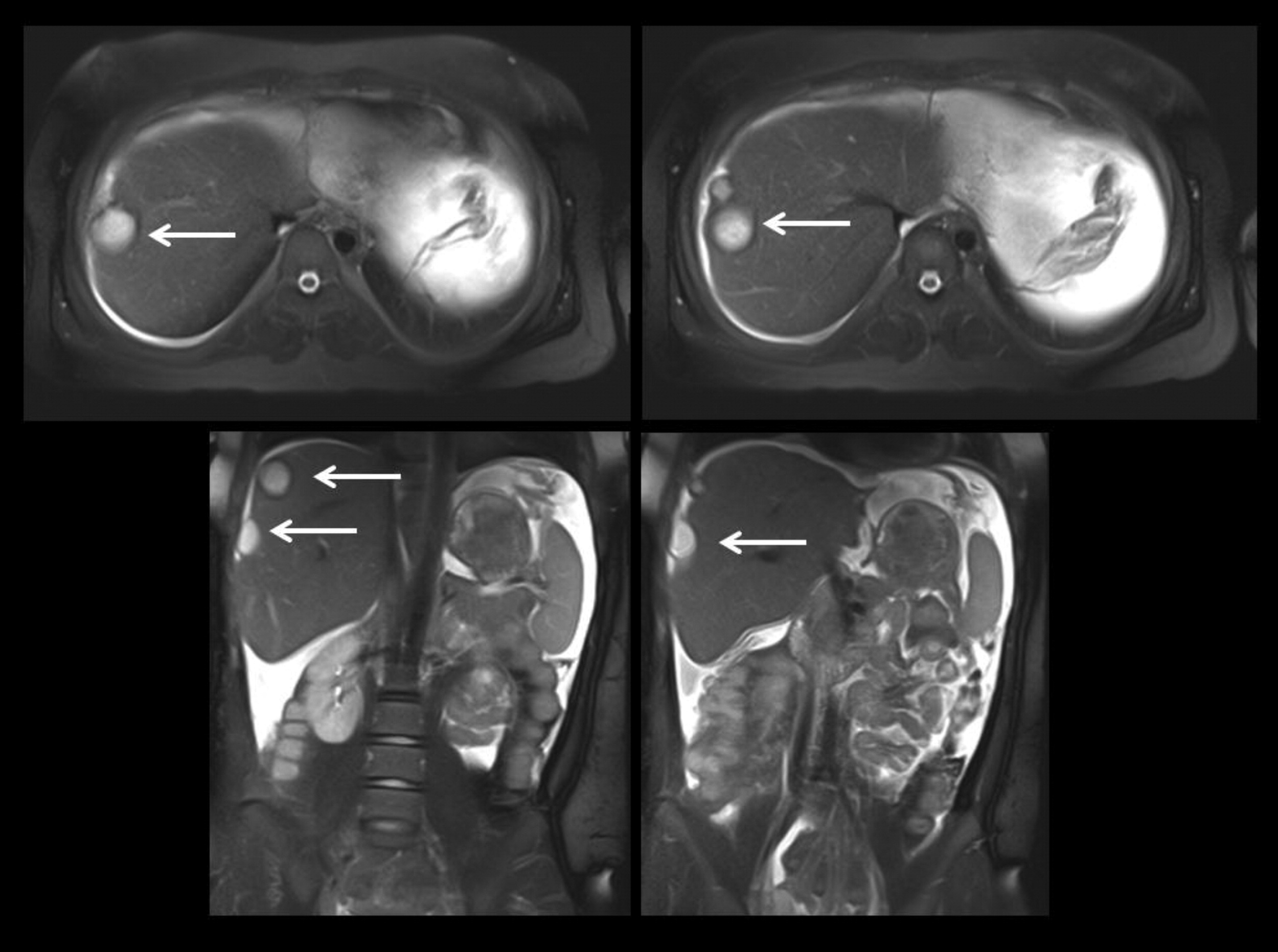

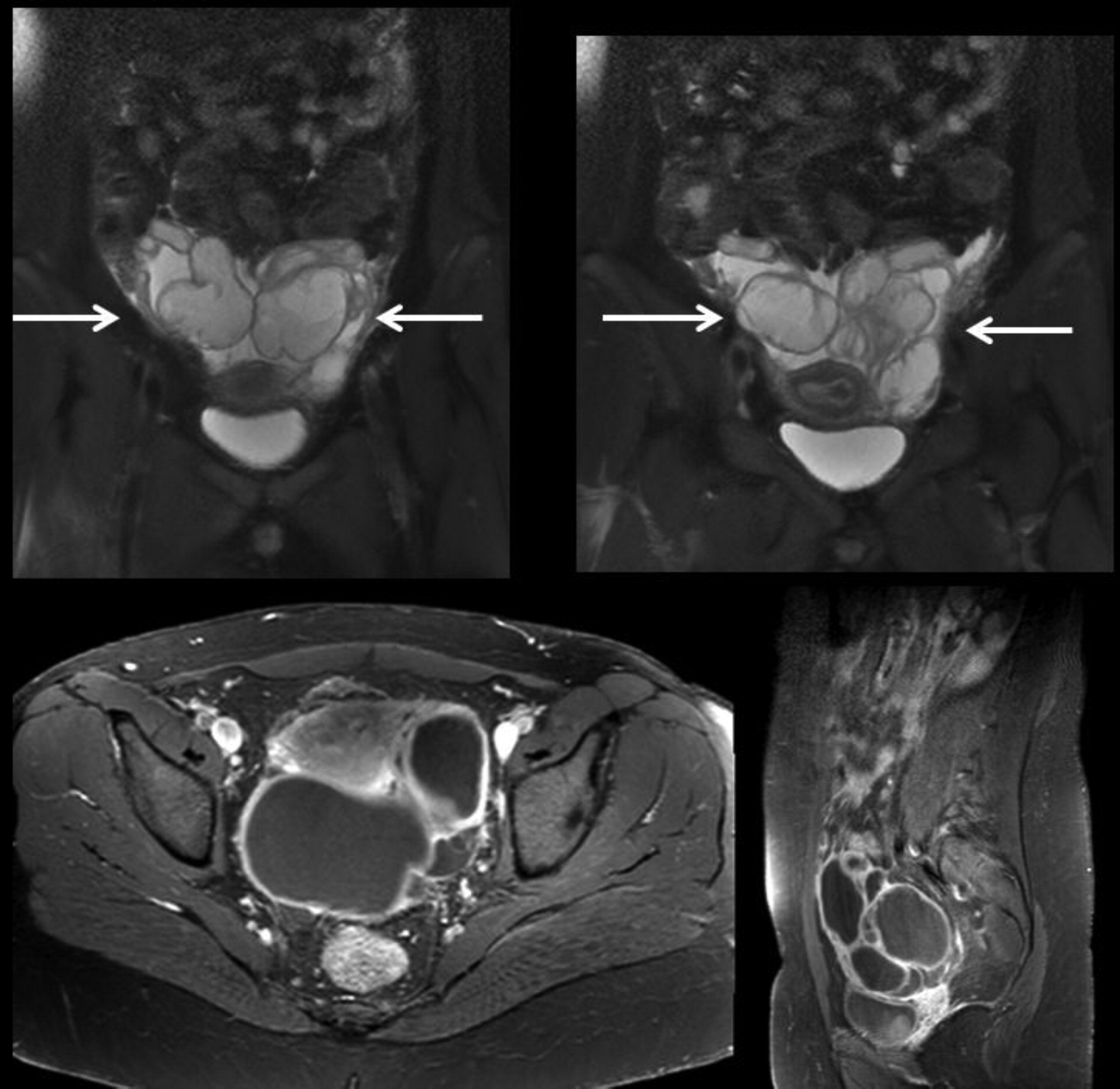

Staphylococcal abscesses of skin, lungs, and other viscera, with minimal signs of inflammation, are classically observed (

Grimbacher et al. 1999a) and demonstrated radiographically in our patients. Abscesses are classified as “cold” abscesses with the absence of erythema and warmth, owing to lack of inflammatory response (

Hill et al. 1974). Another manifestation of an abnormal inflammatory response observed in these patients is the lack of significant fever or inflammatory markers during infections (

Heimall et al. 2010). Patients may present with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in addition to bacterial infections (

Grimbacher et al. 1999a). Reactivation of

Varicella-zoster virus, as shown in patient 3, and infrequently opportunistic infections have been described including

Pneumocystis jiroveci (

Freeman et al. 2006;

Garty et al. 2010),

Cryptococcus (

Jacobs et al. 1984), and

Histoplamosis (

Hutto et al. 1988). In addition to infections of the skin, infants present with an eczematous rash with a skin biopsy demonstrating a predominance of eosinophilic infiltration (

Olaiwan et al. 2011). All 4 of our patients had a description of an eczematous rash early in childhood. Skeletal abnormalities include craniosyntosis (

Hoger et al. 1985), fractures with minimal trauma, osteopenia, hyperextensible joints, and scoliosis, as visualized in the imaging for patient 2 (

Grimbacher et al. 1999a). Patients have higher rates of vascular abnormalities including hypertension, aneurysms involving coronary and cerebral vessels, and vasculitis (

Freeman et al. 2007a,

2011). Additional central nervous system abnormalities described include focal hyperintensities, Chiari 1 malformations, and lacunar infarcts (

Freeman et al. 2007a). Defects of the immune system also lead to higher rates of malignancy, in particular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (

Leonard et al. 2004). It was due to this increased risk of malignancy that patient 4 was referred for further evaluation. Patients with HIES have distinct facial features that become more pronounced with age, particularly after puberty. Features include a prominent forehead, deep-set wide-spaced eyes, broad nasal bridge with wide fleshy nasal tip, coarse appearing skin, and a high arched palate (

Grimbacher et al. 1999a). Delayed shedding of primary teeth leading to double rows of teeth is a unique finding in this patient population (

Grimbacher et al. 1999a). All 4 of the patients described had the characteristic facial features that developed over time in addition to the delayed shedding of primary teeth.

A scoring system combining clinical and laboratory findings has been developed to aid in the diagnosis of HIES (

Grimbacher et al. 1999b). The most common laboratory findings include an elevation in IgE, with the majority of cases over 2000 IU/mL, and eosinophilia (

Grimbacher et al. 1999b). The characteristic elevation in IgE is felt to be an association rather than a contribution to the pathogenesis of HIES. It has been suggested that a defect in the IL-21 receptor signalling results in the elevated IgE levels observed in HIES (

Ozaki et al. 2002). Some patients have humoral defects with poor specific antibody production to protein and polysaccharide immunizations (

Avery et al. 2010) and reduced memory B cells (

Speckmann et al. 2008). Patient 3 had an initial unprotective tetanus titer that responded to repeat vaccination. Additional immune evaluation abnormalities include impaired production of IL-17 (

Milner et al. 2008) and decreased central memory CD4 and CD8 cells (

Siegel et al. 2011).

In conclusion, we documented multiple infectious and noninfectious features associated with STAT3 mutations. Patients presenting with recurrent Staphylococcal infections including lung infections, abscesses of skin and organs, pneumatoceles, mucocutaneous candidiasis, and eczematous rash with associated elevated IgE should be investigated for STAT3 mutation. Detailed radiographic images aid in the diagnosis and management of patients with STAT3-associated HIES.